Dedication of the Sherrill Halbert Lincoln Collection

|

TUESDAY, APRIL 27, 1999, 4:30 P.M.

|

THE CLERK: All rise! Hear ye, hear ye!

All persons having business with the United States District Court for the Eastern District of California will now draw near, give your attention, and you shall be heard. The Honorable William B. Shubb, Chief Judge, presiding.

CHIEF JUDGE SHUBB: Good afternoon, ladies and

gentlemen. Welcome to the dedication of the Sherrill

Halbert Lincoln collection.

CHIEF JUDGE SHUBB: Good afternoon, ladies and

gentlemen. Welcome to the dedication of the Sherrill

Halbert Lincoln collection.

I think most of you know us. If not, let me introduce the judges of our court. To my left, Judge Lawrence K. Karlton; to my right, Judge David F. Levi; behind me, Judge Garland E. Burrell, Jr.; Judge Frank C. Damrell, Jr.; Judge Milton L. Schwartz; and Judge Edward J. Garcia.

Our magistrate judges are in the jury box. They are Chief Magistrate Judge Gregory G. Hollows, Magistrate Judge John F. Moulds, Magistrate Judge Peter A. Nowinski, and Magistrate Judge Dale A. Drozd. Representing our bankruptcy court is Bankruptcy Judge Jane Dickson McKeag.

Also in the box are U.S. Attorney Paul Seave; Eugene Natali, the chief of our Probation Office, and Sue Sorum, the deputy chief; Glenn Thomas, chief of Pretrial Services; Dennis Waks, Chief Assistant Federal Defender; Richard Heltzel, clerk of the Bankruptcy Court; Pat Sandlin, chief deputy clerk; and Jerry Enomoto, U.S. Marshal. I also see some members of their staffs present. Our clerk is Jack Wagner, and our court reporter is Kelly O'Halloran.

We would like to welcome a contingent from McGeorge Law School, along with their dean who will speak to you a little later. And in the front row, we have the Halbert family, who will also be introduced to you a little later. In addition to those, we have many friends of the court, friends of Sherrill Halbert, friends of McGeorge, and friends of Abraham Lincoln here.

Forty years ago, or perhaps in this setting I should say two score years ago, our court sat in the classic courthouse at 8th and I Streets, and Sherrill Halbert presided there as the only district judge in Sacramento.

Some two years later, the court would move to what was then called the new federal building on Capitol Mall. I have heard from several sources, including his good friend Justice Anthony Kennedy and his son Douglas, that Judge Halbert refused to go unless certain changes were made. The story that Justice Kennedy tells relates to the courtroom. He pointed out that in order to enter the courtroom in that building, the judge would have to come from the back and walk through the audience. Can you imagine? One imagines it's like the President entering the Congress to make the State of the Union Address, coming through the audience and shaking hands with the defendant and the prosecutor.

A story that Judge Halbert told had to do with the entrance to the courtroom from the holding cell. When the marshal opened the door from the holding cell, everybody in the courtroom had a clear view of the commode in the holding cell. He also told of how the judge sat so low that when a lawyer addressed the court, the judge had to look up at the lawyer speaking.

Well, eventually changes were made and Judge Halbert was finally dragged to the new courthouse kicking and screaming. The court eventually settled in, and time passed. New judges were appointed, a new district was formed, the months turned into years, years turned into decades, and what was once new became old.

Now our court has moved again to this beautiful courthouse, back home -- back home on I Street and back home to a setting that I think would be more to Judge Halbert's liking.

With the bringing of his Lincoln collection to the new courthouse, part of Judge Halbert's legacy also returns home.

For those of you that may not have known Judge Halbert, let me tell you just a little bit about him. He was born on October 17, 1901, on a sheep ranch south of Porterville, California, that his parents homesteaded in the 1880s. In fact, his father was old enough to remember Abraham Lincoln and told him stories of Lincoln.

After he graduated from Porterville High School, he came north, attended the University of California where he graduated in 1924, and went on to Boalt Hall to attend law school. He graduated from law school in 1927, the same year that he married his wife Verna.

He then moved back to Tulare County where he became a deputy district attorney. In those days, you didn't practice full time in a district attorney's office, so he also had a private practice and handled just about everything.

While he was practicing in Tulare County, he became active in politics and got to know some other district attorneys around the state, one of whom was Earl Warren. In 1942, when World War II broke out, Sherrill Halbert received a telephone call from his former colleague, Earl Warren, who was now Attorney General. He said, "Sherrill, with the war, all of my young men have left the office, and I drastically need your help. Can you come to work for me as a deputy attorney general?" Judge Halbert replied, "Yes, I can do that. How soon would you need me?" The Attorney General said, "How about Monday?"

Telling the story later, the judge said he just gave up his practice and moved to San Francisco to become a deputy attorney general. He was later in a San Francisco law firm for a short time, but he longed to get back to the valley. So he left San Francisco and went to work in the District Attorney's Office in Stanislaus County. While he was there, some of his friends mounted a grass-roots movement to appoint him to the Superior Court, but it didn't happen. So he resigned himself to staying in the District Attorney's Office, and he ran for district attorney and was elected.

Shortly after he was elected district attorney, he received a call from Earl Warren, and he said, "Sherrill, I think it's time you become a Superior Court judge." So from 1949 to 1954, he was a judge of the Stanislaus County Superior Court.

On August 26, 1954, he became a United States District Judge here in Sacramento. He served on this court until he took senior status in 1969, and eventually retired in 1985. He moved to Marin County where he lived until he passed away in 1991.

Besides his interest in Lincoln, he was active in the Sacramento Camellia Festival, the Pioneer Society, and the Pony Express Centennial Celebration.

I first met Judge Halbert sometime in the winter of 1962-1963. I was a third year law school student at the time at Boalt Hall, and the dean told me there was an opportunity to interview with a federal judge for a clerkship. I seized the opportunity and agreed to meet with the judge on a Saturday at the dean's office in Berkeley.

I was waiting in front of the office for the judge. You have to know that I had never met a judge before that day except in my moot court argument. I never even knew any lawyers. I didn't know what a judge looked like. I was waiting at the top of the stairs as several people came up wondering whether each of them was the judge. But when I saw this man start to come up the stairs, I knew this was the judge. He was tall, square jaw, iron gray hair, and confident in appearance.

I interviewed with him, and he invited me to come to Sacramento.

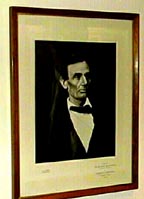

When I visited him in Sacramento about a week

later, I still remember the impressions I got of those

chambers. As you walked into the chambers, in his

waiting area there was a picture of Abraham Lincoln. He

was proud to point out that that was a print from the

original negative. That picture is downstairs, and you

will be able to see it this afternoon.

When I visited him in Sacramento about a week

later, I still remember the impressions I got of those

chambers. As you walked into the chambers, in his

waiting area there was a picture of Abraham Lincoln. He

was proud to point out that that was a print from the

original negative. That picture is downstairs, and you

will be able to see it this afternoon.

When you entered his chambers at that time, the building was new, there was a smell of fresh leather, the carpets were new, and the wood was new. He had paperweights all around the office, and you are going to see some of those in the Lincoln collection. And on the wall, there was a collection of Lincoln books. I thought at that time that was the entire collection. Little did I know that it was but a small part of it. I knew at that moment that I met a real judge.

Judge Halbert reflected some of the differences in culture between the big cities of the Bay Area and Southern California, on the one hand, and the more rural communities of the Sacramento and San Joaquin Valleys on the other. The thing that, in my mind, most typifies that is some of the folksy sayings he used to use.

When he wanted to keep the pressure on, especially on attorneys, or to keep the situation under control, he would say, "You've got to keep them up to the snubbing post."

When he wanted to urge somebody to make a decision, he would say, "They have to fish or cut bait." Later he changed that to, "They have to fish, cut bait, or go ashore." I guess he wanted to give them a third option.

Whenever it was too late to turn back on a situation, he would say, "Well, the fat's in the fire."

One of my favorites was, "If you want to ride in the parlor car, you have to pay parlor car prices." He would use that when a recalcitrant defendant would refuse to be tried before the United States Commissioner, which was the predecessor of the U.S. Magistrate, and later the U.S. Magistrate judges. He would tell them that they would get a fair trial in the District Court, but if they were found guilty, instead of a $5 fine, they might have to pay a $50 fine.

And perhaps my most favorite is one that I use all the time. I've used it to the media, and I've used it to lawyers in connection with this building. He said, "Anything with more moving parts than a crowbar is bound to break down."

Although he had the rural culture, he also had the tastes of a gentleman in the old tradition. I remember when he took his afternoon break from trial, he had his secretary bring him tea. She didn't just bring it in a paper cup. It came in a china teapot with a china cup. And sitting in my office next door to his, I could hear the china rattling as he had his tea in the afternoon.

He also had great respect for the court staff. I am told that hardly a day passed when he didn't make a point of visiting the clerk's office and saying something to everybody there. Judge Halbert would appreciate seeing so many members of the clerk's office here today.

He also respected his probation officers, which at that time were the same as Pretrial Services officers. He valued their advice, but he didn't put them on the spot. He didn't ask for written recommendations. He listened to them, but he didn't want the lawyers to be able to put the pressure on the probation officers. He accepted that responsibility himself.

Judge Halbert is remembered as a practical judge, a no-nonsense judge. He is not generally thought of as a scholar or a legal theorist. But there was another side to this tough prosecutor, this tough judge. He had a very strong judicial philosophy that guided him like an internal gyroscope. It was a philosophy which at that time was not very popular. You have to understand that most of the popular jurists of that day were what we would call today judicial activists. And he eschewed what he called "judicial legislation."

Shortly after he took the bench in 1956, he took the opportunity to express his philosophy in an opinion that he wrote. He didn't have a law clerk write this opinion. He wrote it himself. I would like to read to you just a few passages from that opinion. These are not quotes that he found from some Supreme Court justice or someone else. These are the words of Sherrill Halbert himself expressing his judicial philosophy.

He said, "The power to declare what the law shall be belongs to the legislative branch of the government; the power to declare what the law is, or has been, belongs to the judicial branch of the government. . . . Neither of these branches of the government may invade the province of the other. . . . The courts declare and enforce the law, but they do not make the law. . . . The legislative department alone has the duty of making laws.

"[A] Court that judicially legislates," he said, "commits an obvious violation of the Constitution itself. For a court to usurp legislative power in violation of the affirmative edicts of the Constitution is more reprehensible than an unconstitutional act done by an individual, or individuals, who are unskilled in the law and who are under no oath to uphold, protect, and defend the Constitution. The mere fact that a court does an act in violation of the Constitution does not give the act done any more dignity or moral force than it would have had if it had been done by another.

"Courts that assume that they have the omnipotent wisdom which gives them the power to determine what is good or bad for the people, even against the wishes of the people, are talking in terms of, and acting in direct conformity with modern day totalitarianism, and are taking steps toward a dictatorship or oligarchy, both of which are completely foreign and offensive to our form of government, which is a government of the laws and not of men." [In re Shear, 139 F.Supp. 217, 220-222 (N.D.Cal. 1956).]

Those were the courageous words of a strong judge.

Of course, he was also a Lincoln scholar. We know that. His collection of published materials on Abraham Lincoln was said to be one of the most complete, if not the most complete, in the West. I went down this morning and I looked at them, and I tried to count the books. There must be more than a thousand books there on Abraham Lincoln. Of course, that is what brings us here today.

When he retired, he donated his entire Lincoln collection to McGeorge Law School. It is not just happenstance that Judge Halbert chose McGeorge as the beneficiary of his Lincoln collection. He was a longtime friend of McGeorge and a friend of former Dean Gordon Schaber.

I would now like to call upon the current Dean Gerald Caplan to make a few remarks on behalf of McGeorge.

DEAN CAPLAN: Thank you very much, Judge Shubb. Members of the court, members of the Halbert family, distinguished guests:

I know this is an especially meaningful occasion for Judge Shubb. You saw the importance of the Lincoln collection, the Lincoln memorabilia, when you served as Judge Halbert's clerk for two years following your graduation from law school. And now, 35 years later, you and your judicial colleagues are giving a distinctive tribute to this timeless treasure, and it will be housed in the spacious, state-of-the-art library.

It's been a long time since I made an appearance in Federal Court, and never under more pleasing circumstances, and never in such a handsome facility. You're also providing a well-deserved, meaningful tribute to Judge Halbert.

I won't traverse the record of his professional career, but I want to make a few notes regarding his connection with McGeorge.

When Judge Halbert presented his Lincoln

collection to McGeorge, he explained that Abraham

Lincoln was greatly admired by members of his family.

His grandfather, a Missourian, Dr. Joel Halbert, was a

staunch Union man and supported Abraham Lincoln for

president in 1860. Judge Halbert's father was old

enough to serve briefly with Union forces during the

Civil War, and he, too, was a great admirer of President

Lincoln.

When Judge Halbert presented his Lincoln

collection to McGeorge, he explained that Abraham

Lincoln was greatly admired by members of his family.

His grandfather, a Missourian, Dr. Joel Halbert, was a

staunch Union man and supported Abraham Lincoln for

president in 1860. Judge Halbert's father was old

enough to serve briefly with Union forces during the

Civil War, and he, too, was a great admirer of President

Lincoln.

As a child, Judge Halbert frequently was exposed to commendations of President Lincoln in glowing terms. As a high school student, he was asked along with his classmates to write an essay on some prominent American. And it won't surprise most of you in this room that he chose Abraham Lincoln. When he couldn't find a suitable biography in the school library, he went to the local bookstore, and for 50 cents he bought the one-volume biography of Lincoln by John Nicolay. This biography sparked his interest in building his Lincoln collection as a lifetime avocation. And the original volume by Nocolay is included in this collection which totals 1,247 items, 878 of which are published works.

I didn't count them, but I am indebted to our fine librarians who did. Many of these are autographed by authors and include numbered copies as collected items.

Judge Halbert is recognized for having personally visited virtually every site where Lincoln lived and/or was involved in notable activity. And he himself expressed the view that excepting Shakespeare, a well-known British playwright, Abraham Lincoln's mastery of the English language was exceeded by none.

Judge Halbert was troubled because Lincoln's life was so closely identified with his presidency, and he felt that insufficient attention was given to Lincoln's long career as a lawyer. Lincoln, as we know, conducted his practice in a modest office above the federal courtroom in the Eighth Judicial Circuit in Springfield, Illinois. His furniture included one small desk, a table, a sofa, half dozen plain wooden chairs, and a few enclosed shelves for books. The floor was rarely scrubbed. He prepared cases for the federal courts, the Illinois Supreme Court, and rode circuit for several months twice a year.

He also made it clear that upon the conclusion of his presidency, he would "go right back on practicing law as if nothing ever happened."

Lincoln remains as one of the most popular figures in American history. There are over 14,000 titles on every aspect of his life in the Library of Congress. And a computer search revealed 26,604 references, with the number steadily increasing.

As dean, it is my distinct privilege to represent the McGeorge School of Law and to have made arrangements with my librarian, Katherine Henderson, to loan Judge Sherrill Halbert's Lincoln collection as an addition to the living history of our justice system so beautifully displayed in the library below.

It is appropriate, I believe, also to recognize the vital role that Judge Halbert served in the early life of the McGeorge School of Law. He was chairman of the board until we merged with the University of the Pacific. He was a member of the advisory committee. He was a member of the regents of the University of the Pacific. So it's my pleasure to share this moment with you.

And perhaps saving the most important for last, but I want to give my deep appreciation for the work of the librarians, particularly Susanne Plies. I hope it's not inappropriate for me to ask you to stand and get the recognition you deserve. And, of course, our librarian Katherine Henderson.

Thank you very much, your Honor.

© 2001 United States District Court for the Eastern District of California Historical Society.